Human language uses arbitrary sounds that are then formed into patterns with common meanings. Distinct groups of people create a supply of words and systems for their use. The Hawaiian people shaped an abundant vocabulary, though no written form of their language existed in the precontact period. They utilized ʻōlelo (oral language) in elaborate hula (dances), mele (music), mo‘olelo (stories/legends), and oli (chants).

The Christian missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), based in Boston, sent the first group of missionaries to Hawaiʻi in 1820. The New Englanders arrived with their printing press. Like missionaries to various locations in Asia, the Middle East, and the Pacific, the ministers in Hawaiʻi came with a rudimentary understanding of the language, the intent to learn it, to create a written form, and then to teach people to read and write. They wanted them to read the Scriptures.

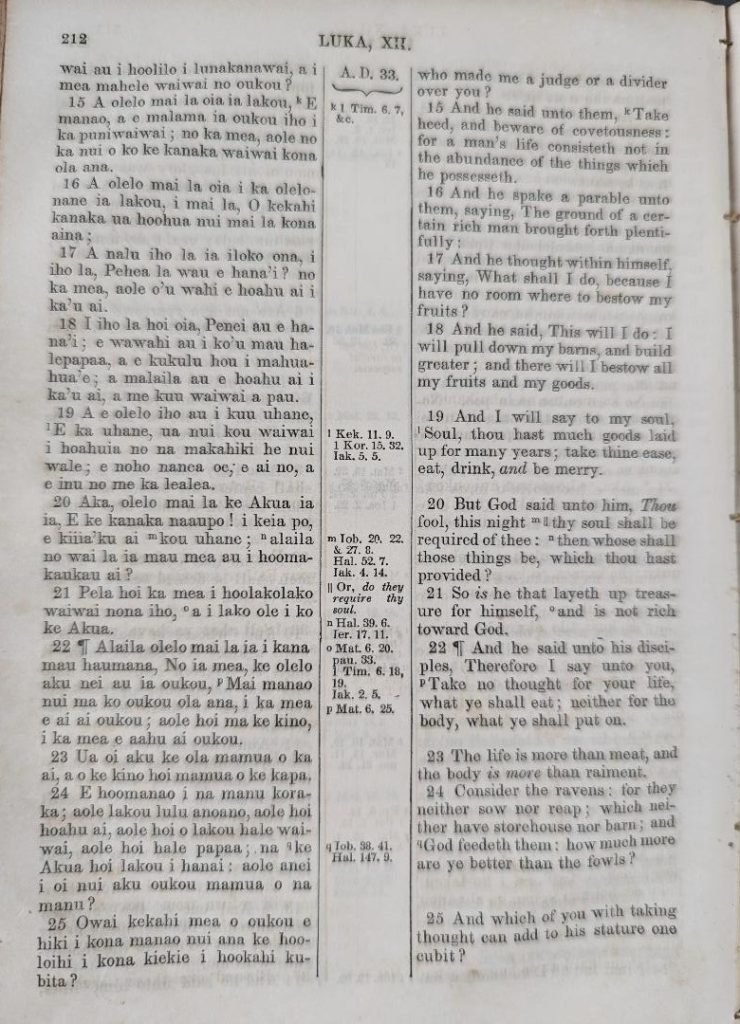

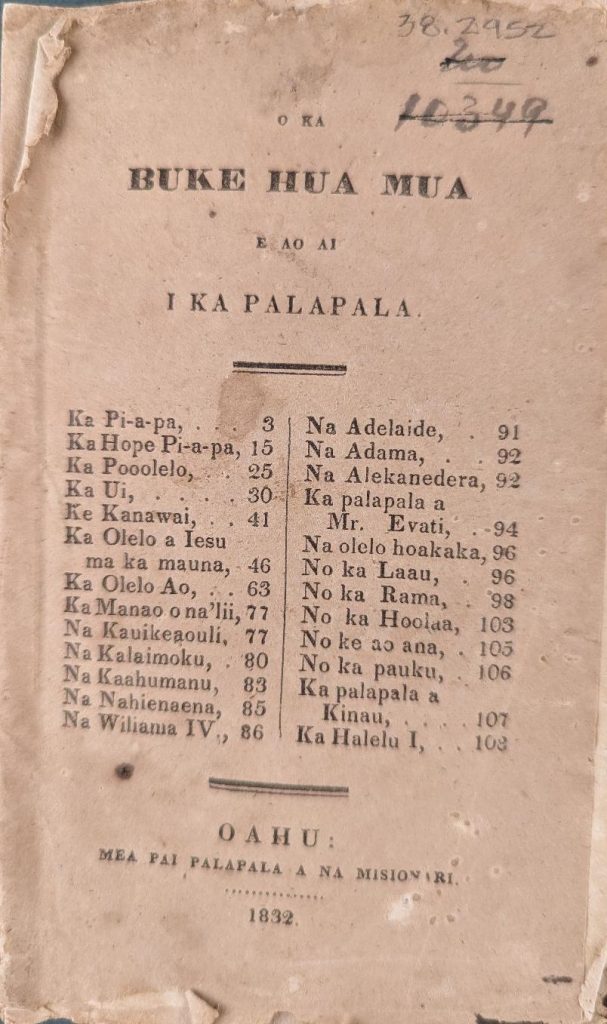

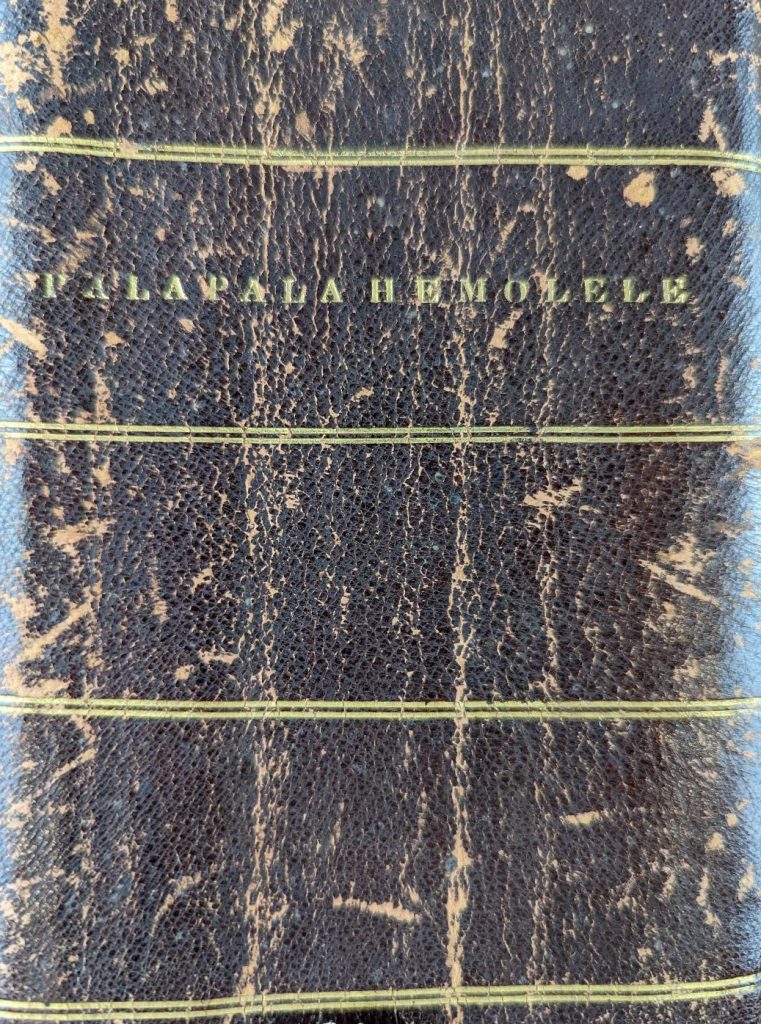

Hawaiian leaders wanted their people to engage with the world. They joined with the missionaries in developing a written form of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi using Latin characters. Even as the language continued to be standardized, the mission press printed a variety of books: a reader (1822), the Christian Scriptures (1832), the newspaper Ka Lama Hawaii (1834), and the complete Bible (1839).

The following books are from the period of 1832 to 1859. The Lyman Museum preserves more than 150 Hawaiian language books as well as primary documents in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. The Archives is open for research by appointment. Learn more at https://lymanmuseum.org/archives/.

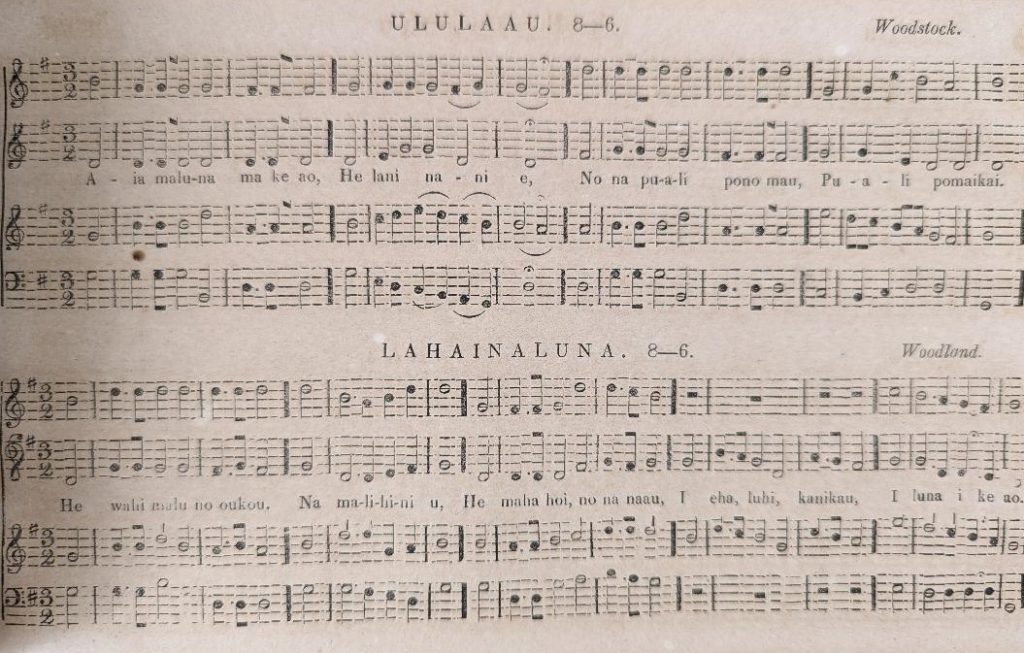

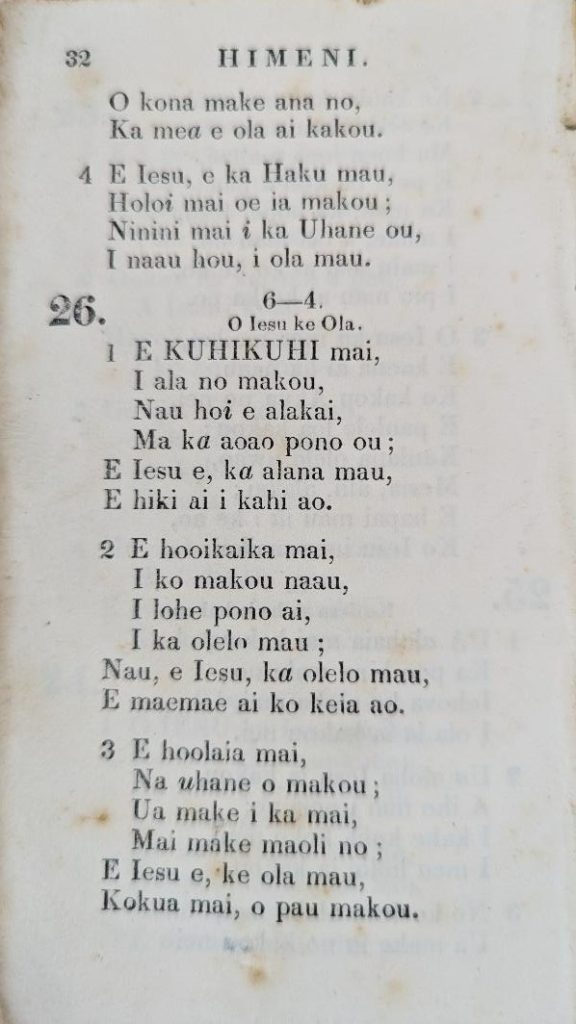

Lorenzo Lyons or Makua Laiana (1807–1886), a missionary with the ABCFM, became a prolific and well-known songwriter who wrote more than 600 hymns in the Hawaiian language. Lyons helped found fourteen churches, in the area surrounding Waimea on Hawaiʻi Island.