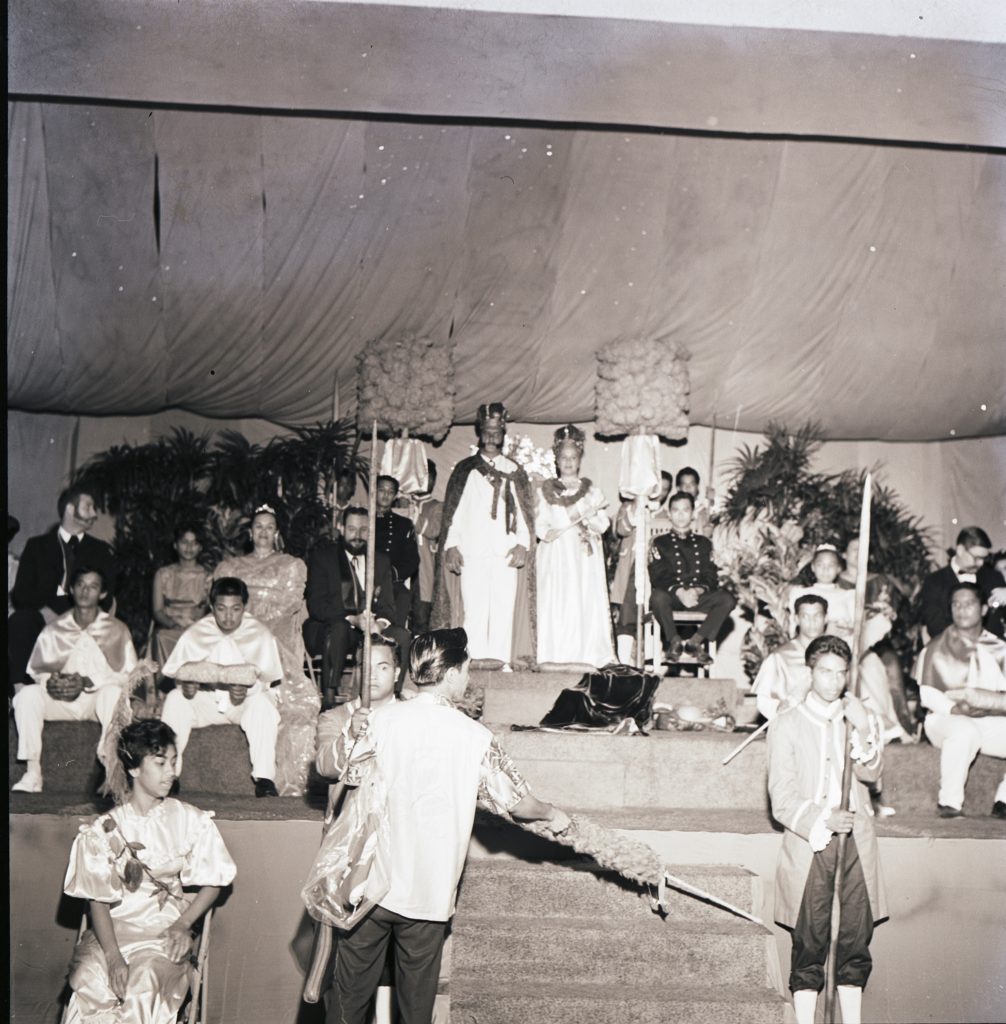

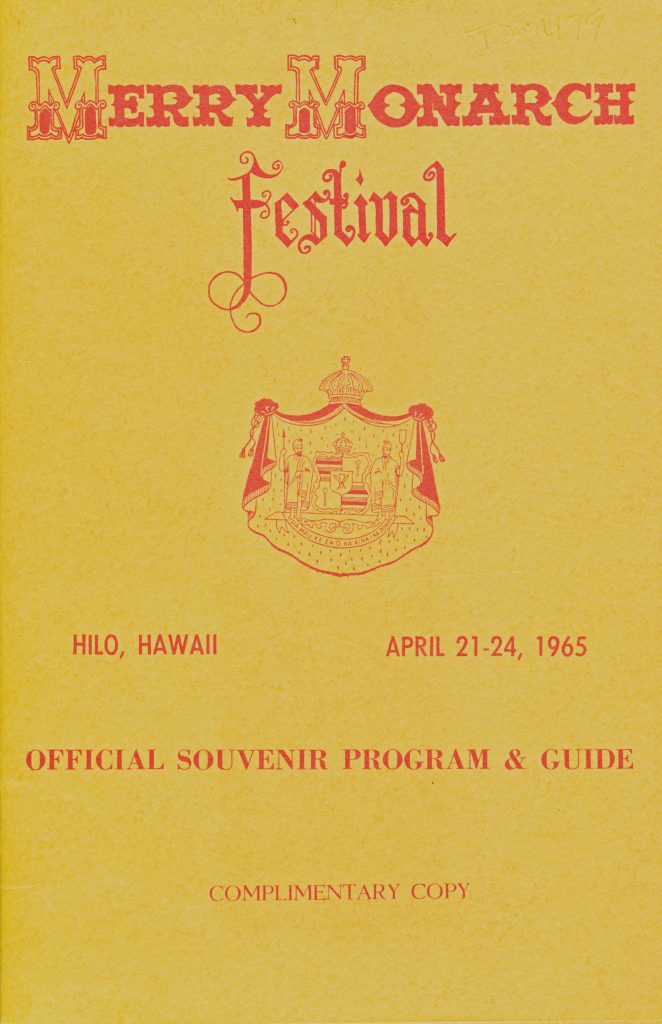

Each Spring people gather in Hilo for the annual Merrie Monarch Festival, a celebration of hula. The event perpetuates many aspects of Hawaiian culture.

Hawaiians used hula with oli (chants) and mo‘olelo (legends) to tell stories. The movements of hula conveyed ideas about creation, genealogy, migrations, and traditions. Ceremonies at a heiau, or stone platform temple, often included dances to honor a Hawaiian divinity or prominent aliʻi (chief).

In the 19th century Christian missionaries sought to change the local religion and culture of the islands. Some of the missionaries viewed hula as immoral. Kaʻahumanu, a Christian convert and queen regent, banned public hula performances in 1830. People widely ignored the law and hula continued to be taught and practiced in private, especially in rural areas.

Moʻi (King) David Laʻamea Kalākaua encouraged the revival of many cultural practices such as he‘e nalu (surfing) and lua (martial arts) during his reign from 1874 to 1891. The King encouraged hula groups and invited them to perform at ʻIolani Palace even as opponents and foreigners criticized him.

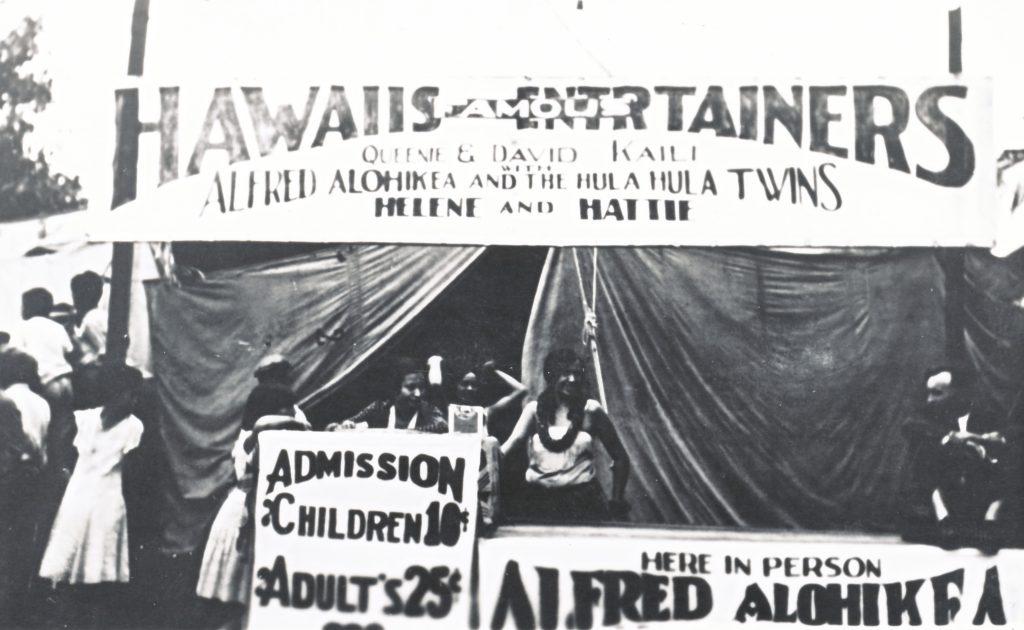

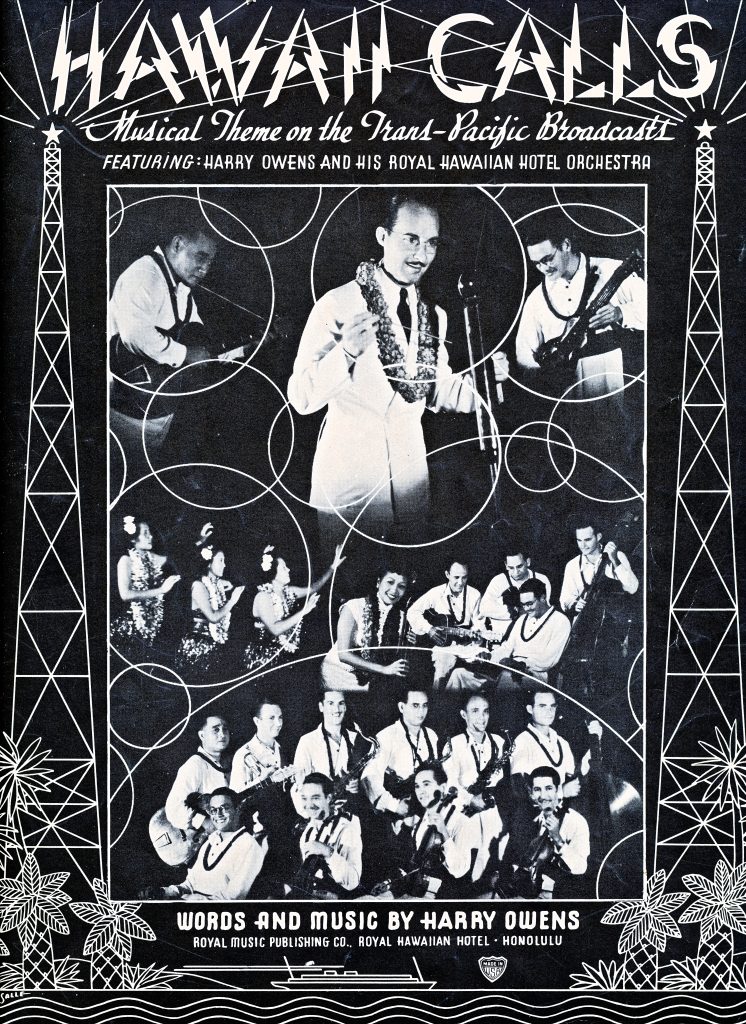

In the 20th century, groups began to offer hula performances for tourists and American soldiers. In 1971 Hilo residents, under the leadership of Dottie Thompson, made hula competitions the focus of the Merrie Monarch Festival. Hula hālau (schools) from across the state and around the world perform kahiko, or traditional dance, and ‘auana, or modern hula. Audiences watch in person or view TV coverage of the competitions.

The Lyman Museum preserves many hula-related photographs. To see more, the Archives is open for research by appointment. Learn more at https://lymanmuseum.org/archives/.