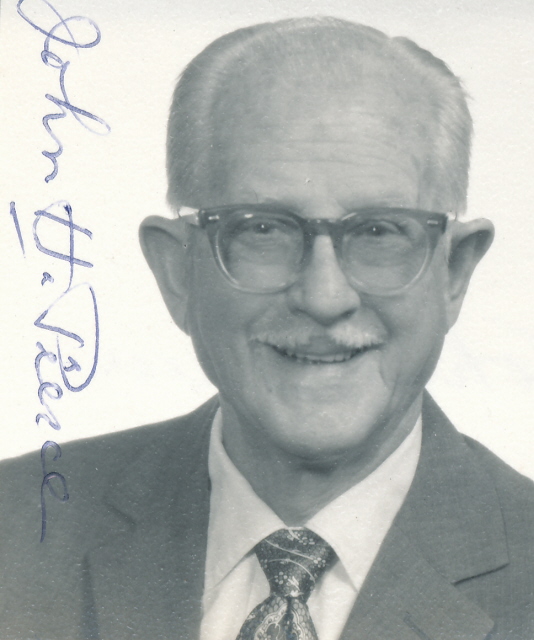

The John Howard Pierce Photograph Collection contains Pierce’s surviving body of work—tens of thousands of photographic negatives and prints taken from the time he began work at the Hawaii Tribune-Herald in 1951 through 1973.

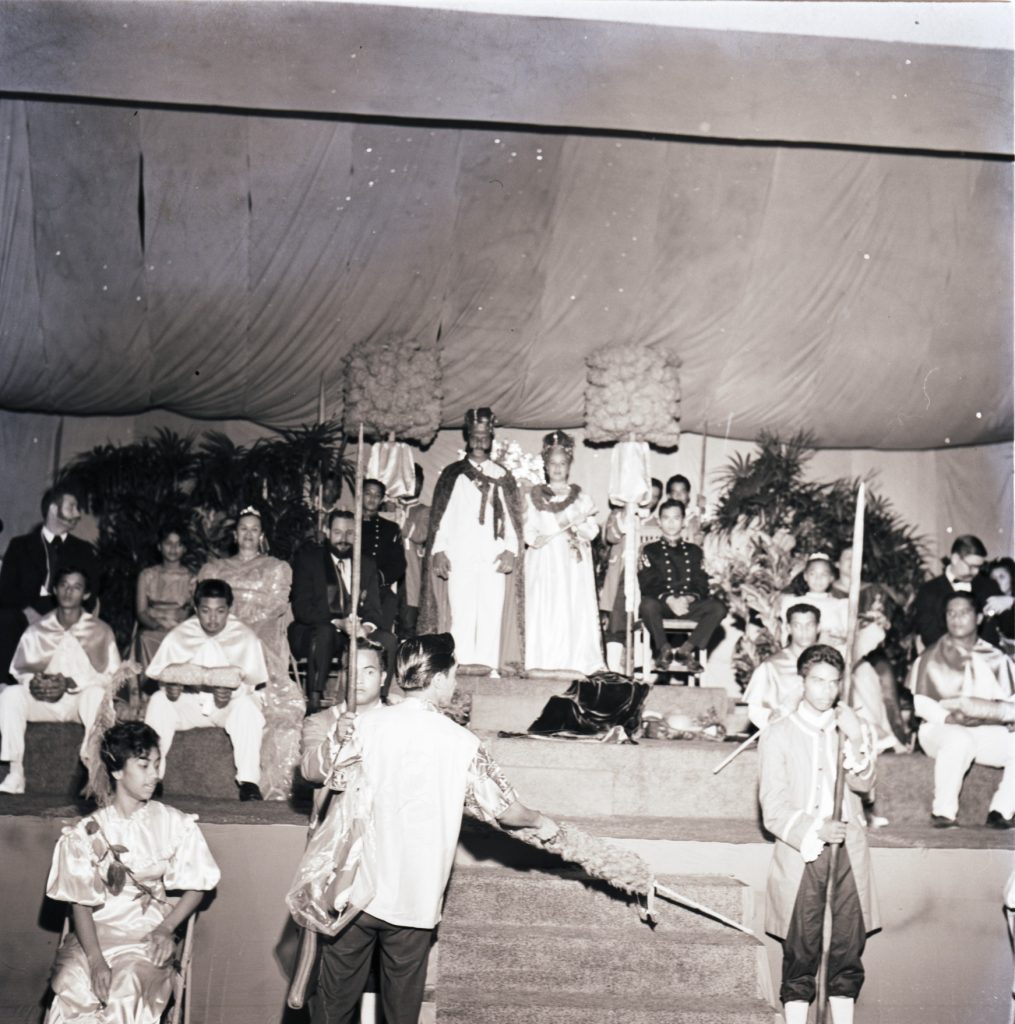

The collection’s significance lies in the years covered and the extensive range of subjects captured. Pierce and his camera bore witness to many community activities and development on Hawaiʻi Island during a historically important period of tremendous growth and change—those years before and after statehood. This expansive and comprehensive view of Hawai‘i Island from construction, economic development, and tourism to a burgeoning Hawaiian Renaissance, makes the collection an invaluable contribution not only to Hawai’i Island’s story, but to Hawaiʻi’s historical record.

The collection was given to the Lyman Museum in 2007. The Photo Identification Project is an ongoing effort to recruit help from the community to solve these mysteries. Most of the images in the collection have little information beyond date. With the help of the public, thousands of Pierce photographs have already been identified. This ID Project is only one step toward the goal of sharing digital images with the larger public.

To learn more about the Pierce Photo Collection or to help identify photographs, contact the Archives for a research appointment: https://lymanmuseum.org/archives/.

Note: Hawaiian diacritical marks comprise just two symbols: the ʻokina (glottal stop) and the kahakō (macron). We use them with Hawaiian place names, but do not add them to proper names if a family or a company does not use them.

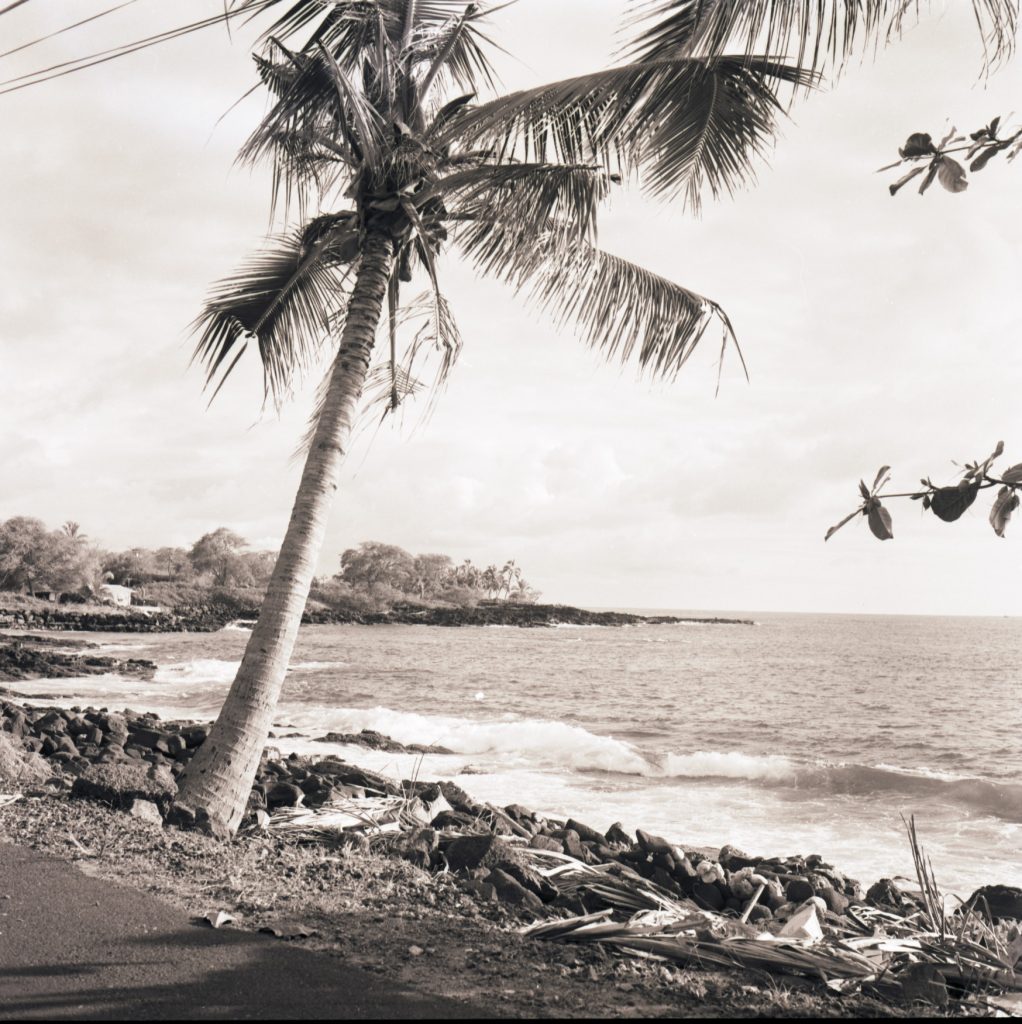

The Kailua-Kona coastline, site of the future Royal Kona Resort before construction, October 21, 1966 and the Kailua-Kona coastline, with the Royal Kona Resort constructed, March 2, 1968. Building construction across the Island boomed in the wake of statehood in 1959 and the devastating tsunami in Hilo in 1960.